Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority, but to their inhumanity and fear. (-From My Dungeon Shook)

2025 will soon end but the political chaos continues. Here in Puerto Rico and throughout the Caribbean region, we witness the obscene escalation of US militarization. Looking back to this year’s inception, its infamous inaugurations, and everything historic and systemic that has brought us to this point, it is easy to feel disoriented. Focusing on our immediate surroundings and communities becomes more crucial. In times of war, one must consider: How has humanity evolved (or not)? How is the violent patriarchy still running the show from its macro levels of war to its day-to-day micro aggressions?

Having taken extended pauses from social media this year (for reasons already stated) there is much that I have not shared. But considering that December marks the anniversary of his 1987 transition into ancestorhood, I feel compelled to close out this year reflecting and sharing on empire, exile and rematriation within the context of the Divine Masculine: James Baldwin conversation we hosted in February 2025 at CucubaNación, here in Mayagüez. Why am I referencing the lessons of Baldwin’s legacy on this blog about Boricua rematriation? Like Baldwin, I do not view my own or our collective experience within a vacuum. I honor ancestral lessons and apply them. Before living on this archipelago, I was born and raised in Brooklyn, politicized by our people’s struggle. By “our people” I mean all nations occupied by that empire: Native American, African American, Mexican/ Chicanx, Boricua and more. It also turns out that James Baldwin had his own connections to Puerto Rico.

Ask any Mexican, any Puerto Rican, any black man, any poor person – ask the wretched how they fare in the halls of justice, and then you will know, not whether or not the country is just, but whether or not it has any love for justice, or any concept of it. It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.” (-James Baldwin from No Name in the Street)

The US was long heralded as migration destination supreme. To leave the place everyone insisted you must stay in or migrate to caused shock and confusion, or you were simply labeled as crazy. Enter 2025: Social media feeds blast images of folks packing their pickups and driving across the southern border in what some call “self-deportation.” I think about countless families who have been living in Aztlán long before the US seized half of México’s lands under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. How many have been “deported” from their own ancestral lands over the past century?! More 2025 social media posts show rich “Americans” fleeing to other continents, while others promote businesses luring the frightened to pursue passports overseas.

Exit and exile

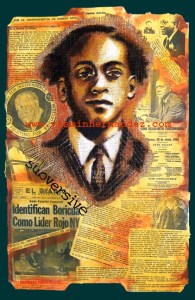

Having left the states eleven years ago, I began this year tuning out the political shock tactics and distractions by offering a series of intimate spaces to gather for inspirational, replenishing, in-person conversations. Called to lift the names of men who had inspired me, who were working to dismantle racism, colonialism, the patriarchy, along with my usual programming I created another series, Divine Masculine. Legendary African American writer, novelist, essayist, playwright, civil rights activist, James Baldwin embodied a deep love for his people and revealed the US in ways it just wasn’t wanting to be revealed. Having recently painted his portrait, I planned a workshop dedicated to his legacy.

One of the details that most intrigued me about Baldwin’s journey was his choice to leave. In 1948, as the Un-American Committee hearings continued in the US (same year the Gag Law was imposed in its colony of Puerto Rico, outlawing any pro-independence sentiments), a 24-year-old James Baldwin left. He decided to make his life outside of the US, believing that to create sustainably and effectively he would have to leave the homophobic, white supremacist society of that empire. For this he sought exile in Paris. In A Dinner in France, 1973: Josephine Baker, James Baldwin, and a Very Young Henry Louis Gates, Jr, Harmony Holiday on the Public-Private Tensions of Black Life in America, Holiday also highlights black life beyond America, and the US media’s attempts to suppress such possibilities. Henry Louis Gates, Jr had been commissioned by Time magazine to interview the two greats in France, yet, as Holiday writes:

Time claimed to have rejected Gates’s account of this conversation because its subjects weren’t relevant enough for the pages of their elevated gossip columns in that specific year; but what they really rejected was this glimpse of Black Americans existing outside of the fame-makers’ imaginations. Time refused to spread that rumor and give it more momentum. America resents the Black people who get away, from W.E.B. DuBois to Paul Robeson, from Jimmy to Josephine, always attempting to make a scandal of the pursuit of sanity and self-knowledge that’s really at the center of exile. And so, few of us do get out. This modest gathering in the south of France in 1973 proves there is life after America, that Black Americans are not required to stick it out, that there are aspects of Black private life the media will never acknowledge, in the US or abroad, life that we must seek out and understand if we want to love our mutual heroes beyond parasitic worship.

Repatriation/ Rematriation

Long before the second inauguration of a certain president; before Hurricane María aid; pandemic flight out of the metropolis; or escape from fascism made it “trending”, like Baker (1924) and Baldwin (1948), I had fled the US (2014). The US media still made sure to keep a lid on any success stories of folks leaving. My few references came through my Brooklyn soundtrack of roots reggae repatriation odes, or Brand Nubian’s Black Star Line: “Marcus Garvey had the idea back in the days, Doin’ for self, keepin’ the wealth.” I didn’t just want out; I wanted a return to one of my ancestral sources. I was called to the islands on which I had long centered my work, the birthplace of my parents. Boricua references for such a journey also came through poetry and song, but they spoke of an unrequited dream of a return never realized. Corretjer’s poem Boricua en la Luna, later composed into song by Roy Brown, mentions a laborer who literally worked himself to death before he could return to the archipelago: “y de tanto trabajar se quedó sin regresar, reventó en un taller.” Then there are the accounts of attempts by the Young Lords Party and the Nuyorican Poets to translate their revolutionary work to the archipelago. Aside from the media blackout of those returning, arriving and staying, our own people would let us know that the attempt would be bleak at best, and that those attempting were effin’ crazy. I chose crazy.

Rematriation as a liberation practice rises from the disruption caused by empire forcibly displacing us from our homes on this Earth—as seen with Indigenous People of Turtle Island and all the “Americas”, with the Transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans, to most of the global Chamorro population living outside of their native Guam versus within it, and many more examples. In the case of this archipelago, still facing displacement by US colonialism for over a century and a quarter, part of the rematriation journey is acknowledging the profound ironies of persisting in, and/ or serving the empire. That is to say: there are some of us who engage in decolonial work from within the empire, just as there are those who have never left the archipelago but play their colonial part serving the empire from right here on our ancestral islands. This is how the most recent wave of US remilitarization went down with the quickness, with the cooperation of the colonial governor.

Rematriation is a choice, a practice that oftentimes defies/ transcends location. Yet Rematriation, as related to the archipelago of Puerto Rico, gets reduced on social media as a simple move back home. In my years here, I’ve learned that there is nothing simple about Rematriation, and it is never simply a move. It is an ancestral call, a realignment, a liberation practice rooted in one’s mind, bones and spirit first. At its root, rematriation is returning to the womb. This doesn’t mean the move back to the homeland, but restoring the matriarchal practices that centered humanity, nature, earth, spirit, cosmos—all things suppressed by the patriarchy. We know what the patriarchy has done to women, children, nature, for centuries. Not enough is discussed around what it has done to men themselves, nor the boys violated by it while conditioned to embody it. (Not to mention the women who uphold it by imposing patriarchal standards in child rearing and relationships.)

As a gay, black man, Baldwin delved into these issues and tried to flee US racism, patriarchy and homophobia. He did not pursue a move to the motherland of motherlands that is the whole continent of Africa, as did Maya Angelou, Nina Simone and other contemporaries of his. Instead, he lived in France and Turkey and traveled beyond. The article Escape from America, published on the website of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, states, “Baldwin became a world citizen,” and that “he went several times to Puerto Rico.” Yet during his travels and time abroad, he didn’t find true deliverance from what he experienced in the US but a deeper realization:

It turned out that the question of who I was was not solved because I had removed myself from the social forces which menaced me—anyway, these forces had become interior, and I had dragged them across the ocean with me. The question of who I was had at last become a personal question, and the answer was to be found in me. (-From Nobody Knows my Name)

This realization reveals another layer of rematriation as a return to one’s true self. The first homeland is the body, the self. We question and navigate all these forces that seek to exert control over us and negotiate our liberation from these (by various means). Those seeking a return to our original homelands are ultimately searching for a return to our truest, freest selves. In leaving, Baldwin returned to himself. This offered him a sharper sight to observe and reveal all that the empire continued to suppress, and the ways we could overturn and transcend it regardless of our geopolitical location. It also affirmed, contrary to the narrative long sold, that the US is not the only place on Earth where people should feel free and safe, and if they don’t, they could pursue life elsewhere. Rematriation as a hashtag by Boricuas could benefit from a deeper exploration into reasons we are displaced from the archipelago in the first place; the reasons we feel the urge to leave the states if that is where we were displaced to; and can certainly benefit from an historic look into the conditions of the Native American, African American and Mexican/ Chicanx nations occupied within that empire and the parallels to our own experience. Add to this the indigenous peoples of Hawai’i, Alaska, Guam and the Mariana Islands as well as the Virgin Islands. This of course is considering the US empire, but Boricuas have long built solidarities with these communities and beyond to Palestine, Japan and others affected by colonialism, displacement and militarism.

What the World has done to my Brother

2025 certainly cemented and justified the journeys of those of us who upped and left (not that we were needing permission). For however shocked some folks might be at the events of this past year, this has always been the grim legacy of the US. Baldwin was born and raised in Harlem where Jim Crow laws, the KKK, lynchings, forced detainments and deportations were not dark legacies of a distant south, but living histories, pathologies, that seeped into the whole US experience. Heralded as a crucial voice of the Civil Rights movement, his rage and grief surrounding the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. inspired the unfinished book-turned source for the Raoul Peck documentary, I am Not Your Negro. It offers visuals of Baldwin detailing a visit to Puerto Rico, driving under a sunny blue sky, listening to a Puerto Rican music station. After a sudden interruption of the music, he hears the radio announcer share the tragic news of the murder of his friend, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, just 37 years old.

I know what the world has done to my brother and how narrowly he has survived it. And I know, which is much worse, and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives…. (-From My Dungeon Shook.)

With this imposed normalization of violence, indigenous, black, brown bodies across the planet continue to be lost, oftentimes ungrieved, forgotten by the collective. The Black Lives Matters movement sounded the alarm on the reescalation of a problem that had never been solved. Between 2020 and the mass losses related to whatever COVID was before too fading into media oblivion; the continued Nakba waged on the Palestinian people; slave-conditions adults and children in the Congo labor through, die through to supply the cobalt sustaining the world’s dependency on technological devices; the bombings and killing of Venezuelan civilians; and the detainment/ deportation/ disappearance of countless people in the US: Death at mass scale is normalized/ televised/ streamed, liked/ shared/ subscribed.

It would seem, unless one looks more deeply at the phenomenon, that most people are able to delude themselves and get through their lives quite happily. But I still believe that the unexamined life is not worth living: and I know that self-delusion, in the service of no matter how small or lofty cause, is a price no writer can afford. His subject is himself and the world and it requires every ounce of stamina he can summon to attempt to look on himself and the world as they are. (-From Nobody Knows my Name)

Lifting Legacies: Divine Masculine

As a sister to a brother that is no longer with us and as a mother to two teen sons, I examine the dehumanizing/ desensitizing/ discarding of our men. The Divine Masculine series lifts necessary legacies. As an artist, each portrait I paint requires that I research their biographical information, read their writings, study their work, their images. These workshops are an extension of my creative practice. A few months before, I had painted a portrait of James Baldwin alongside another literary inspiration, Piri Thomas. Their books appear side by side on a shelf of the library of la Casa Museo Filiberto Ojeda Rios, where the painting debuted as part of the Afro.Bori.Libertaria exhibition that opened there on September 23rd, 2024, in collaboration with my friend, fellow painter Damary Burgos who conceived the idea. That exhibition, inspired by the library collection of Puerto Rican revolutionary Filiberto Ojeda Ríos, and its countless books on black liberation, is what sparked the idea of painting these two literary groundbreakers, together.

There are ancestors that I have researched and painted repeatedly, like Julia de Burgos, featured in a political poetry series, Julia Libertaria. Overlapping with that series, the first Divine Masculine workshop featured Afro Puerto Rican writer, activist, journalist, Jesús Colón, one of my biggest writing inspirations, the earliest source of all things Brooklyn-Boricua. Colón had arrived in Brooklyn from Puerto Rico in 1917 when he was just 16 years old, same age my father was when he arrived alone in Brooklyn from Ponce. During the Jesús Colón workshop I announced that the next Divine Masculine session would be dedicated to James Baldwin. Present that evening was Aimee Montoya of Vive Borikén. After my announcement, she shared that her friend, Trevor Baldwin, James’ nephew, would be visiting Puerto Rico and that we should speak. Trevor, a keeper of Baldwin’s legacy, godson to Maya Angelou, had worked diligently on the centennial of his uncle’s birth, commemorated in August of 2024. Speaking to Trevor over the phone, I wasn’t

surprised to learn that, though committed to working in his home community, he also spends time abroad, continuing this legacy.

Thinking on this Baldwin legacy and Baldwin’s home where he passed in St. Paul de Vence, France, brings to mind another ancestor that also lived and passed in France. Ramón Emeterio Betances, nineteenth century Puerto Rican and Dominican physician, abolitionist and revolutionary, author of el Grito de Lares, lived on and off in France since childhood and transitioned there before his remains were eventually returned to his birthplace of Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. Along my journey, I realized that most of my heroes had spent time in either chosen or imposed exile. Their time living and working in other countries expanded the worldviews that marked their contributions to their people and beyond. Their model teaches us to deeply embrace the whole history of humanity and migration. The United States seems to be the only place that frowns upon the experience of living abroad, being from abroad, and being multilingual.

Like Betances, Baldwin was his own kind of revolutionary. He wasn’t always beloved by his own people and the mainstream. The Humanity Archive author and podcast host Jermaine Fowler offers a powerful summary of Baldwin’s life and legacy:

In 1957, he came back. The fire came with him.

The FBI opened a file on Baldwin in 1959 and never closed it. One thousand eight hundred eighty-four pages by the time they were done. Malcolm X, who preached armed self-defense, got twenty-three hundred. Baldwin got nearly as many for writing essays. Hoover’s men tracked his movements, logged his friendships, noted every border he crossed. The Bureau watched a man with a typewriter the way it watched revolutionaries with guns.

White America’s silence on Baldwin makes sense. But it wasn’t only white America that silenced him.

The movement silenced him too.

Rainbow Signs and The Fire Next Time

Contemplating the theme of the divine masculine, what has always stood out was Baldwin’s “My Dungeon Shook: A Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation” from his book, The Fire Next Time. The letter, written to his fifteen-year-old nephew (also named James), offers reflections and advice on growing up as a young black man in the US.

For here you were, Big James, named for me- you were a big baby, I was not—here you were; to be loved. To be loved baby, hard, at once, and forever, to strengthen you against the loveless world…

You were not expected to aspire to excellence: you were expected to make peace with mediocrity.

A series of solidarities and synchronicities made this event possible. Yes, I painted a portrait of James Baldwin, paired the portrait with that of Piri Thomas, as in “No Name in the Street” meets “Beale Street” meets “Down these Mean Streets;” part Jimmy’s “Rainbow Signs” of “Fire[s] Next Time;” part Piri’s, “Behold the rainbow that is you”; When I announced the Divine Masculine event on James Baldwin, Aimee was there and shared that she was friends with Trevor Baldwin, his nephew who would just so happen to be visiting during the time of the event; These are the ancestral convergences of this Puerto Rican Portal! You breathe in gratitude for the moment.

Sometimes we get an idea or inspiration and we don’t follow it through, dismissing it as a random thought. But some of these thoughts are seeds long ago planted by our ancestors. They’re looking to us to water them, to sprout, to grow, to harvest them. Following through on the idea for these Divine Masculine workshops opened avenues to an expanded dialogue. Having Trevor present at this event brought the gift of deeper context and personal anecdotes on Baldwin’s life, work, and legacy. These ancestors motivate us, drive and animate us with their stories. They call us to lift their names and voices, stories and experiences; to study them, learn from them, strategize with them for all the work they’ve already put in; all the manuals and instructions they’ve already left us; all the tools and resources that they gathered for us. When we do, they ensure that all synchronizes to advance the work.

Aimee hosted two other events with Trevor that weekend. One was a screening of the film adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk at Taller Libertá, just a few blocks away, also in Mayagüez. In the novel, James Baldwin draws connections between the poverty lived in Puerto Rico and that of Harlem: “I had never seen it like that before. Never. I don’t speak no Spanish and they don’t speak no English. But we on the same garbage dump. For the same reason.”

Aimee’s second event was a deeper conversation on Puerto Rico’s political condition. Following a conversation on capitalist colonialism, which always leaves me feeling like a heated, crazy artist, I was blessed with a gift from Trevor: a black mug with red and green letters with yellow highlights. They read:

“Artists are here to disturb the peace.” -James Baldwin.

A most necessary, affirming message in the colors of luciérnagas/ fireflies: Colors of Marcus Garvey’s Pan Africanism/ Black Liberation. Colors of the palette I use for some of my CucubaNación paintings to assert Puerto Rico’s place within the greater Black Liberation struggle, the greater African Diaspora. Colors I used to paint James Baldwin and Piri Thomas. I’m not sure Trevor realized how monumental a gift it was. For the many times parts of my Diasporic self-have felt unseen, unwelcomed on my ancestral lands. The same can be said for all who were in dialogue with him during this visit as they shared memories of their first encounters with Baldwin’s work and its impact. This is another layer of rematriation and migration—walking whole in the solidarities, the lessons of struggle, and expanded awareness we gained in our journeys. It is knowing, like Filiberto’s library, that liberation is global and intersectional, from Harlem, to Brooklyn, to Borikén, to Betances, to Baldwin and beyond.

A most necessary, affirming message in the colors of luciérnagas/ fireflies: Colors of Marcus Garvey’s Pan Africanism/ Black Liberation. Colors of the palette I use for some of my CucubaNación paintings to assert Puerto Rico’s place within the greater Black Liberation struggle, the greater African Diaspora. Colors I used to paint James Baldwin and Piri Thomas. I’m not sure Trevor realized how monumental a gift it was. For the many times parts of my Diasporic self-have felt unseen, unwelcomed on my ancestral lands. The same can be said for all who were in dialogue with him during this visit as they shared memories of their first encounters with Baldwin’s work and its impact. This is another layer of rematriation and migration—walking whole in the solidarities, the lessons of struggle, and expanded awareness we gained in our journeys. It is knowing, like Filiberto’s library, that liberation is global and intersectional, from Harlem, to Brooklyn, to Borikén, to Betances, to Baldwin and beyond.

I think of the quote on this mug and recognize that disrupting the peace also means securing our own peace, even if it means we leave. It is never “mak[ing] peace with mediocrity.” It is never conforming to the imposed structures that secure peace for some by force while refusing to extend peace to so many others. It is the commitment to always advocate for one’s own authentic truth openly. Yet here, with rapid remilitarization, the struggle continues.

God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water, the fire next time.

If next time would be the fire, then that time is already here. We opened this year with a white, north American tourist setting fire to local businesses in Cabo Rojo, then fleeing back to the states. A few days later the Los Angeles area wildfires started burning. By the end of the month, two new administrations, here and there, had taken office and were burning everything down.

If next time would be the fire, then that time is already here. We opened this year with a white, north American tourist setting fire to local businesses in Cabo Rojo, then fleeing back to the states. A few days later the Los Angeles area wildfires started burning. By the end of the month, two new administrations, here and there, had taken office and were burning everything down.

On January 25th, my family traveled to Betances’ Cabo Rojo, not to see the ruins of a US tourist-turned arsonist but for an observation night of la Sociedad Astronómica de Puerto Rico where they had set up several telescopes in this area known to be one of the darkest in the main island. We would later appreciate the planetary alignment and Jupiter’s moons via one of those telescopes, but the show began from the moment we parked our car along a dirt road. Folks were already respecting the rules of turning off their lights and only entering with a red lantern. As we set up our lanterns in the trunk our oldest son screamed, just fifteen at the time, same age as Baldwin’s nephew when he dedicated the letter to him. We turned around to find him pointing at an unmistakable, large, green fireball shooting across the sky. A random meteor that left the entire parking area breathless. Standing under that black sky unable to see the crowds of people against the faint red glow of lanterns, under lasers the astronomers pointed to mark Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, I was in awe of the calm, the stillness, the peace and safety I felt there. It reminded me of being in Hurricane Maria’s bright, peaceful eye after homegirl’s eye wall had pounded the living daylights out of us and would again. Empire’s fire rages all around us, but we burn our own sacred fires within.

In that painting of Piri Thomas and James Baldwin, in gold calligraphy I include this quote that James Baldwin uses in his book The Fire Next Time. I also used a Piri Thomas quote from his poem, Softly Puerto Rican, where he says: “And behold the rainbow that is you!” Piri Thomas, Boricua/ Cubano, born in East Harlem in 1928; James Baldwin was born in 1924 at Harlem Hospital where Julia de Burgos passed in 1953. James Baldwin visited Puerto Rico that same year. These intersecting ancestors ask that we be rainbows through the fire, brilliant, vibrant colors in all their saturation and luminosity.

At our James Baldwin event, someone had asked, “Where do we go from here, where is the hope?” Another person present shared, “Well the sign was given, he wrote the prophesy.” Another brother who was present privately shared that he’s been lighting bonfires since childhood, something he shared with his father. The divine masculine as sun, fire, flame moves fathers, sons, brothers, uncles, nephews, awakens us all. That event had the most cis men present of any other event at CucubaNación, usually attended by women and queer folx. There have been multiple masculinities in myriad expressions coming through the space. Through the fire resounds the light of a letter an uncle wrote to his nephew, letting him know that he is loved. Even though we are born among the flames, these expressions of love are the ultimate weapon in the fight for justice, for liberation that lies ahead. The fire, as embodied by Baldwin, (or Uncle Jimmy as he was called by Trevor and other nephews) is the liberation, the transcendence that comes when we stop modeling the empire’s lovelessness and pursuit of power to ignite instead our sacred love of self and each other.

At our James Baldwin event, someone had asked, “Where do we go from here, where is the hope?” Another person present shared, “Well the sign was given, he wrote the prophesy.” Another brother who was present privately shared that he’s been lighting bonfires since childhood, something he shared with his father. The divine masculine as sun, fire, flame moves fathers, sons, brothers, uncles, nephews, awakens us all. That event had the most cis men present of any other event at CucubaNación, usually attended by women and queer folx. There have been multiple masculinities in myriad expressions coming through the space. Through the fire resounds the light of a letter an uncle wrote to his nephew, letting him know that he is loved. Even though we are born among the flames, these expressions of love are the ultimate weapon in the fight for justice, for liberation that lies ahead. The fire, as embodied by Baldwin, (or Uncle Jimmy as he was called by Trevor and other nephews) is the liberation, the transcendence that comes when we stop modeling the empire’s lovelessness and pursuit of power to ignite instead our sacred love of self and each other.

James Baldwin ¡Presente!

August 2, 1924, Harlem, NYC – December 1, 1987, St. Paul de Vence, France

Yasmín Hernández is a Brooklyn-born and raised/ Borikén-based artist, writer and activist centered on liberation. CucubaNación is her Mayaguez-based art space dedicated to the liberatory light lessons of Boricua bioluminescence. With Rematriating Borikén she documents and celebrates the journey back to our essence. For more info visit: yasminhernandez.art .

Leave a comment